For a straight week protesters around Miami-Dade County have taken to the streets in the City of Miami, Miami Shores, Miami Beach, Miami Lakes and North Miami shouting, “Black Lives Matter” and demanding accountability from local police departments.

Miami George Floyd protest. Photo credit: Woosler DelisfortLike many of the other protests happening right now around the country, they were sparked by the brutal killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis where a police officer pressed his knee into Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds — until Floyd could no longer breathe.

Miami George Floyd protest. Photo credit: Woosler DelisfortLike many of the other protests happening right now around the country, they were sparked by the brutal killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis where a police officer pressed his knee into Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds — until Floyd could no longer breathe.

Miami-area elected officials and police departments have denounced the killing of Floyd calling it an injustice; feel-good photos of local law enforcement officers kneeling with protesters drew praise, but despite the slew of condemnations and officers’ seeming moment of solidarity with protesters —these actions stop short of examining the violence and systemic racism within local police departments. That, for Black protesters in Miami-Dade, they are not just marching for Floyd and a singular injustice that happened “over there.” They’re also marching for themselves, their community and against the police violence and injustices in the criminal legal system here.

We’ve been here before.

Forty years ago this year, Black communities in Miami erupted after four white police officers were acquitted in the fatal beating of Arthur McDuffie. In May 1980, McDuffie, an affable insurance salesman and Marine Corps veteran was pulled over after a short police chase on his motorcycle in Miami. At least four officers, possibly more, knocked him off his bike and pummeled him with heavy duty flashlights and batons. The officers immediately attempted to cover up their crime by staging the scene as if McDuffie had been in an accident. Four days later, McDuffie died from his injuries

His mom, Eula McDuffie, cried, “They beat my son like a dog. They beat him because he was riding a motorcycle and because he was black.”

Dr. Ronald Wright, the county’s chief medical examiner at the time testified that McDuffie’s injuries were so extensive, they were consistent with someone who’d fallen from a four-story building. Wright said of the 3,600 autopsies he’d completed, McDuffie’s was the worst brain damage he’d ever seen.

When the officers were acquitted a few months later, Black Miami took to the streets and set Liberty City ablaze. The National Guard was called in and officials vowed to study what led to one of the deadliest riots in this country’s history—18 people dead, hundreds injured and more than $100 million in damages. Photo Credit: Nadege Green

Photo Credit: Nadege Green

It’s become an American tradition for politicians to seek out dense reports on what causes Black uprisings — from 1919 to present — only to ignore the findings outlining why Black people are angry, tired and fed up with an unjust and deadly system.

Two years after the 1980 Miami uprisings, the United States Commission on Civil Rights issued a report on what led to Miami burning, “Confronting Racial Isolation in Miami.”

“The McDuffie verdict was perceived as more than just an isolated failure of the criminal justice system. To the black community and many others in Miami and elsewhere, the McDuffie verdict appeared to be the final proof that the criminal justice system in Dade County was incapable of condemning official violence against blacks,” according to the 1980 report.

Forty years later, many of the findings and observations from the report still stand.

At the beginning of 2020, the City of Miami police police department was under federal oversight for a spate of fatal shootings — seven Black men were killed over a period of eight months from 2010 to 2011. In their report, the U.S. Department of Justice found Miami police officers have a pattern of using excessive force in officer-involved shootings, poor tactical decisions by officers and inadequate internal investigations.

Photo Credit: Nadege GreenAnd even when the department tries to hold its own accountable, it falls short.

Photo Credit: Nadege GreenAnd even when the department tries to hold its own accountable, it falls short.

Travis McNeil, 28, was one of the Black men shot and killed by a Miami officer. During a 2011 traffic stop, Officer Reynaldo Goyos said McNeil reached for something in the car making him fear for his life. There were no weapons found in the car, just two cell phones near McNeil’s feet.

The Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office declined to prosecute the case, but the police department fired Goyos for “unjustifiable deadly force.” Goyos challenged his firing through arbitration and a year later, despite his bosses objections, got his job back with $72,000 in back pay.

Travis McNeil’s mom upon learning that Goyos, the man who killed her son would get his job back, said, “I wish it was that easy to get my son back.”

In the 1980 Commission on Civil Rights report, close attention was paid to the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s office and its relationship with the police departments it had to investigate. The report found after examining the office’s police investigations, “[t]he State Attorney appears to have aligned herself on the side of the police even when such an alignment is insupportable.”

In Miami-Dade contemporary cases by the state attorney’s office have also drawn similar critiques over potential biases toward law enforcement.

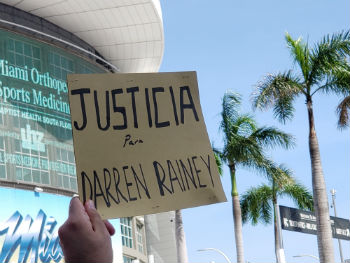

This week, at one of the George Floyd protests in downtown Miami someone held up a sign in Spanish calling for “Justicia para Darren Rainey,” justice for Darren Rainey.

Rainey was a mentally ill Black inmate at Dade Correctional Institute serving a sentence for cocaine possession. A 2017 Miami Herald investigation found Rainey was placed in a burning hot shower that had been rigged by corrections officers to punish inmates. Ninety minutes later, Rainey was found lifeless in the shower with severe burns to his body after being locked in there to “boil” as some of the inmates described.

It took three years after Rainey’s death for an official autopsy to be released and the medical examiner reported there was no trauma to Rainey’s body — despite autopsy photos that appear to show otherwise and inmate testimony that Rainey’s skin was curling off his body like “fruit roll-ups,” according to the Miami Herald.

The Miami-Dade State Attorney’s office declined to press charges against the corrections officers.

Forty years after the Miami McDuffie Riots and in a moment of national mourning for George Floyd, Miami-Dade is marching because police violence isn’t an isolated problem.

That was evidenced this week in a virtual Miami-Dade County Commission Public Safety Committe meeting where more than 200 people signed up to speak. The county commission had an item on the agenda expressing outrage over the killing of George Floyd. Miami-Dade constituents rightfully asked their elected officials to express the same outrage over police killings and police violence locally. And speaker after speaker after speaker pleaded with the commission to defund the police department to instead invest in community services.

Miami-Dade continues to march and organize against police violence because it’s our problem too.

Dyma Loving was violently thrown onto the ground and arrested by a Miami-Dade police officer after she was the one who called the police for help after a neighbor threatened her with a gun.

Charles Kinsey was shot with his hand in the air by a North Miami police officer while trying to protect his client with autism who ran away. Officers explained they were trying to shoot the man with autism who was holding a toy car in his hand not Kinsey.

Lavall Hall was having a mental health episode when his mom called Miami Gardens police to help. His mom said officers approached with aggression and her son did not understand their commands in his mental state. At some point during confrontation with police Hall had a broomstick in his hand. One of the responding officers shot and killed him.

Clarens Desrouleaux was deported to Haiti because Biscayne Park police framed him for a robbery he never committed. Further investigations found Biscayne Park police officers had a directive from then police chief Raimundo Atesiano to target innocent Black men walking through the neighborhood. Officers lied on arrest affidavits to pin burglaries on at least seven random Black men they knew were innocent of the crimes.

Sebastian Gregory was 16-years old when a Miami-Dade police officer stopped him for walking. Sebastian was shot six times in the back because the officer said he thought the aluminum bat he carried was a gun. Sebastian was left paralyzed in one leg and with chronic pain as a result of the shooting. He died by sucide a few years later. His family said the shooting left him in a state of depression.

Israel Reefa Hernandez was tagging a shuttered McDonald’s building when a Miami Beach police officer chased him and struck him with a taser. Hernandez had an apparent seizure and was pronounced dead less than an hour later. The officers allegedly laughed and high-fived each other after shocking Hernandez, according to witnesses at the scene.

Megan Adamescu was punched in the face and kicked by a Miami Beach police officer .

Jose Trinidad Garcia Alvarado, a migrant farmworker, was handcuffed and in police custody when he was slammed into a concrete wall head first by a Homestead police officer.

Bryan Crespo was already in handcuffs when a Miami-Dade sergeant slapped him in the face. When the officer realized he was being recorded by a camera in the home he tried to tamper with the surveillance system.

Tony Zaldivar was handcuffed and sitting in a City of Miami police officer’s car when an officer jumped on him and punched him.

Raymond Herisse was shot and killed on Miami Beach in a hail of bullets from Miami Beach and Hialeah police officers during Memorial Day weekend for driving dangerously.

Nadege Green (She/Her) is the director of Community Research and Storytelling for the Community Justice Project. Community Justice Project supports grassroots organizing for power, racial justice and human rights with innovative lawyering, research and creative strategy tools. Based in Miami, FL, Community Justice Project is deeply and unapologetically committed to Black and brown communities throughout Florida.